(Or rather, a guide on how not to not be vulnerable)

Context: In 2015, I spoke to strangers about love, during which, vulnerability emerged as one of the most common things everyone spoke about. “For me, love is when I can be vulnerable with someone” – most people had a variation of this statement. I had started asking questions about vulnerability, trying to define it — what does it feel like? When do you feel vulnerable — why do you call that vulnerability? We had made vulnerability scales and plotted our intimacies on them. (I wrote about my conversations on vulnerability here).

Curious, with questions of my own, I experimented with trying to be as vulnerable as I possibly could, only to learn that one cannot be vulnerable, as much as, one can decide not to not be vulnerable. (I wrote about what I learnt about vulnerability by experimenting with it here). Based on some of the comments I received, I decided to write this starter guide for becoming more vulnerable.

[Before I begin, let me state this: I am not an expert on vulnerability. I do read up a lot on it (a list of references included in this blog post), and I have had a chance to play with it and learn. This blog post is more of an invitation to experiment with me. So, please, do let me know how this goes for you!]

Let’s go!

One of the biggest lessons I learnt about vulnerability is that one cannot become vulnerable; one can only decide not to not be vulnerable. In other words, in order to be vulnerable, we need to start peeling off the protective filters so that our innermost, authentic, wholehearted selves become visible. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t ever have filters; just that we don’t put up the filters out of fear, but out of choice.

And in the best case scenario, that would be what you would achieve at the end of this experiment. On board?

Step 1: Plot your starting point

I don’t know if vulnerability feels the same for everyone (I have a feeling it does), but I do know that the things that make you vulnerable are often different for different people. Figure out what your definition and relationship with vulnerability is.

Some questions that I find useful to figure this out are:

- Think of the times you felt most vulnerable. What did you feel?

- Now think of the common themes in those times: What about those situations made you feel vulnerable? Why? What were you scared would happen?

- Think of what the outcomes to those times were: What happened at the end of these situations? When did you land up doing things despite being vulnerable, and when couldn’t you? Why? Were there any people/ relationships/ types of relationships that were common?

- Try and plot these on a number line: on a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is the most vulnerable you think you can be, what is your average vulnerability? What is the highest you have experienced?

(Bonus: If you haven’t seen it already, start with this super popular TED talk by Brene Brown on vulnerability)

Step 2: Start observing your filters

It might not be wise to immediately start blindly peeling off filters/ layers of protection. We use them for a reason. And also, we have been using these filters for so long, that they are almost stuck to us. We need to slowly loosen the grip these filters have on us.

The easiest way to do this is to start noticing when we are putting on filters and to become aware of what it is that we are protecting against. Pay attention to when you stop yourself from doing/ saying/ being something you naturally want to be. Why?

One question I ask myself in these times is: What am I afraid will happen if I am vulnerable (or if I do/ say/ be something)? Why is that such a bad thing/ why am I afraid?

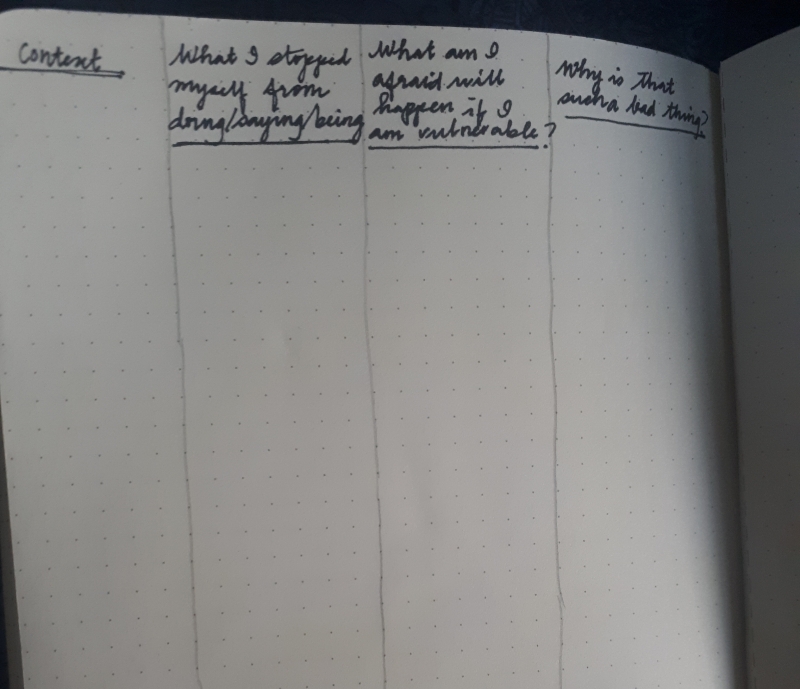

I have a diary that I always carry with me, so I was actually physically making note of each of these whenever I could. A little table at the back of my book with four columns:

Initially, this is feels like a major task, and we aren’t always attentive to the filters. We didn’t know how to distinguish the times of vulnerability from when we were simply choosing one way or the other.

So, I found the following strategy useful:

Start by paying attention when you find yourself having second thoughts about something. Or when you find yourself saying one thing out loud and another thing in your head. Or when you find yourself saying, “not now, “… Initially, you will have to specifically be reminded to do this. After a while though, you will find yourself noticing this all the time.

Another way to do this is to focus on one aspect of your life – either a context, like work or relationships or social occasions, or a certain kinds of situations like when I wanted to say something and you don’t, and start paying attention to the filters you use in these situations.

Either way – once you have enough data about your filters, slowly trends started to emerge. There will be some things you are constantly afraid of, some filters you were using most often. Make note of these.

(Bonus: Here‘s Amanda Palmer being her beautiful self and talking about the art of asking, which is one form of intense vulnerability)

Step 3: Deconstruct and test these fears

Here’s the most important think I have learnt, re-emphasised: the goal isn’t to get rid of the fears but to not let them control our actions. And the second most important lesson: a lot of these fears were based on assumptions I was making, assumptions that may or may not always be true.

Once I began to see the trends in the fears that were driving my behaviours, I started to think about why I was so afraid, often changing my relationship with these fears. I could respect them when they were indeed important for protection without being bound to them.

Sidenote: a little bit of what psychology says about these assumptions

Several of the assumptions underlying all of these fears often came from some experience that had affected me enough to generalise. Martin Seligman, the father of the Positive Psychology movement explains this phenomenon in his book Learned Optimism as “explanatory style”.

“Your habitual way of explaining bad events, your explanatory style, is more than just the words you mouth when you fail. It is a habit of thought, learned in childhood and adolescence. Your explanatory style stems directly from your view of your place in the world – whether you think you are valuable and deserving, or worthless and hopeless” (p.44).

He goes on to state that there are three crucial dimensions to explanatory style, the 3Ps:

Permanence: Whether you believe that the bad events will persist permanently or how often the good events repeat themselves – does this always or never happen, or do you think it happens sometimes?

Pervasiveness: Whether you believe that the cause of the bad event is universal – do you assume it will go this same way in every aspect/ everywhere?

Personalisation: Do you blame yourself when things go wrong? Do bad events affect your sense of worth?

When faced with things going wrong, we must question the assumptions we make about these three Ps:

Will this always last?

Will this affect all aspects of my life?

Am I really to blame?

(This article might be a good starting point to learn more about how your explanatory style affects how the bad events turn into fear. If you want a real life example, here is Sheryl Sandberg talking about it in the context of her process of coping in her Berkeley Commencement address. If you want to read more in detail, Learned Optimism is definitely a great read)

Another reason psychologists have found us to be bound by fears is because of how bad we assume we are going to feel when things go wrong, something that Albert Ellis calls awfulizing/ catastrophizing. We assume that that that feel like the end of the world; which might not really be true.

(A summary of his ideas can be found here, whereas you can read about it in detail in his incredible book A Guide to Rational Living)

So, anyway, what do we do with the fears

Here’s a term we have come to find surprisingly comforting: test it out with more data. Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey, in what they call the “Immunity-to-Change” (ITC) approach, go into detail about how to examine some of the assumptions. In borrowing from what they say, here are some questions you might find useful to think about the fears after you have noticed them:

- Look for contrary evidence: Have there been times when things have gone differently, and actually the opposite of what you feared happened? Or, are there other possible explanations for what could have happened? Being able to add examples when the fear is not true helps reduce the feeling we have that our fear is always true.

- Explore the history: Think a little about why that fear is so overarching in your life. What are some of the memories that have made that fear so important in your life (as against other fears that do not bother you as much)? Being able to understand where the fears come from also make them more reachable to work on.

- Test the assumptions: Run little experiments to see if the assumptions are true. What if you tried to do it the other way one time? These do not have to be wild tests, and you do not have to be testing all the time. But when you feel safe, it’s worth seeing what happens.

(This article can offer a quick lesson on ITC. Their book, Immunity to Change: How to overcome it and unlock the potential in yourself and your organisation is a fantastic reference for thinking about how our assumptions prevent us from making change and how we can over come it. Albert Ellis’ Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy also presents a similar framework called ABC model, which examines it as Activating incident/ adversity, rational and irrational Beliefs underlying it and the Consequences or results of the adversities. You can learn about this in more detail in both Learned Optimism and A Guide to Rational Living.

Evaluate what you learn about your assumptions/ fears after testing them. Are they always true? Could there be other possibilities? Not seeing assumptions/ fears through the lens of absolute can loosen the hold they have on us, and often just that much is enough.

(Bonus: Here’s a hilariously insightful story about facing fears by Jia Jiang who voluntarily planned for 100 days of Rejection – which is such an incredible version of a vulnerability experiment!)

Alternative Step 3: Pay attention to the shoulds

Sometimes, you will notice that the underlying assumption under your fears or actions isn’t a fear but rather a strong “should” that you carry – the belief that you should behave one way or the other. While “shoulds” are useful constructs we inherit from the world around us, it is always useful to see them as guidelines rather than rules, and to choose to abide by them if they make sense to us rather than be bound by them.

Notice how many times you use “should” (or “must”, or “have to”) while listing your fears. Pay attention to when that comes with a value judgement – you should do this if you are a good woman .

It might be useful to spend some time thinking about the genesis of these shoulds, and also which ones make sense to you and which ones cause more damage than good. Same thing about all the ideas about perfection we keep trying to work towards.

You might want to run a few tests for the latter – which of these shoulds and ideas of perfection are healthy for you? And which of these cause mostly just shame when not followed? Please test the latter the same way you test the fears.

(Bonus: this delightful TED talk about the love and embracing the “sort of poetry of deliberate awkwardness” by Yann Dall’Aglio)

Step 4: Start peeling off the layers

When you identify the fears and shoulds and images of perfect that you now feel have a less hold on you and you are willing to shed them when not needed – try that. Pick a safe area in your life. Pick a safe occasion, a safe person – a space where you can try being without that layer. And practice being without it. Practice being courageous. And slowly, it will start to shed.

You don’t have to start by shedding all of it at the same time. Pick your battles. And start building your vulnerability muscles there.

(Bonus: This slightly graphic but lovely TED talk about embrace our “inner girl” by the prolific Eve Ensler)

Step 5: Care for your self

Chances are, a lot of emotions might emerge in the course of all this experimentation and toying with vulnerability. I like using this metaphor to explain this –

you know how babies sometimes cry just because they need some attention? Sometimes, when you are busy, you just need to pick them up and carry on with your work, and they are fine. But you can’t do that all the time. Once in a while, you need to actually play with them.

Our emotions are a lot like that. We usually just pick them up and carry on with our lives. Several of us even manage to tune out the sounds they make. Being vulnerable involves paying attention to them, and once in a while, attending to them.

And that can be stressful. Despite all the risk-taking this experimentation encourages, psychological safety is important. Take care of your self. There are three things I think are essential in self-care if you have to be vulnerable:

- Make sure you have a support system: Find people you trust, people you can make mistakes with, open up to, people who understand you. Tell them you are doing this, and let them support you – by being sounding boards, by being perspective-givers, by giving hugs… whatever support means to you, ask for it.

- Figure out practices that work for you: All of us process things differently, we de-stress differently, we introspect differently. Find the practices that work for you – Do you want to journal? Or use a more physical form of processing like art? Do you meditate? Do you read? Figure that out and use it. You will be discovering new things about yourself and new emotions (that is one test that you are doing this right), so definitely figure out practices for processing the new information.

- Make time: Make time for this processing. For stillness. Put it in the calendar. Switch off your phone. Do what it takes, but don’t run through this. Please.

(Bonus: This beautiful talk by Elizabeth Lesser about the healing process of seeking truth & connection, and taking the time to do it)

Step 6: Repeat

This, is a lifelong process. It will get familiar, if not easy, with time. Keep at it. Keep discovering new things. Keep getting more vulnerable. And I hope you find joy in it.

(Bonus: The fabulous Marina Abramovic’s TED talk about her experiments with vulnerability in her art)

Optional Step 7: Tell me how it went

I am learning too. And I’d love to hear how this goes for you and learn with/from you. Do write to me and let me know how this goes!

Jayati Doshi

7th Oct, 2018. 5:48pm IST

[…] out. If you are interested in trying this out, I compiled some ideas for where you could start in this blog post. It includes list-making, flowcharts of questions and things you can read to learn […]

LikeLike